When people enter into a contract, everything changes. Before the contract is formed, people can change their minds. They can walk away from negotiations, ask for a higher price, or decide to do business with someone else. After the contract is formed, they have to do what they promised.

Contracts are promises that courts will enforce, but courts won’t get involved for just any promise. Courts require that the parties intend to be bound by their promises at the time of their contracting. And they require contracts to be a two-way street. That’s where consideration comes in. Each party has to bring something to the table.

I hesitate to write about consideration because it’s confusing, the law is riddled with exceptions, and consideration usually isn’t at issue in the typical business-to-business transaction. But consideration is important in a sufficient number of contexts — such as when you’re amending a services contract or negotiating a settlement — that I find myself thinking about consideration in my law practice frequently. So I’m compromising with myself and writing a short post to introduce the concept and leaving discussion of the myriad issues that the legal doctrine poses to future consideration.

What is consideration?

Consideration is something of value that a contracting party promises to the other party. In general, consideration comes in two flavors: a benefit that you promise to give the other party and a detriment that you agree to take on. A promise to pay the purchase price for a product would be an example of the former; a promise not to sue someone would be an example of the latter. The Restatement (Second) of Contracts defines consideration as an “act, forbearance, return promise, or creation, modification, or destruction of a legal relationship that is bargained for and given in exchange for the promise” (§ 71).

In most contracts, consideration is a two-way street and the relationship must be analyzed from the point of view of each party. Each is required to provide consideration — a concept often called mutuality — or the contract fails for lack of consideration, and a party who wants to enforce the deal in court will be out of luck.

Although each party has to provide consideration, courts usually won’t delve into whether the deal is fair, so there can be a great disparity in the value of each party’s consideration.

An example of consideration

Here’s a simple example of consideration: A few years ago my wife bought me a used kayak. If we offered to buy the kayak for $400 and for us to pick up the kayak the following day and they accepted, we’d have a contract. (In reality, we didn’t technically have a contract, because I just showed up at the seller’s apartment after a short phone call, took a look at the kayak, gave the seller $400, and took the kayak home. Without future promises, there wasn’t a contract, but that’s a technicality for another day.) The consideration from me was a promise to pay cash and the consideration from the seller was a promise to deliver the kayak. Each promised something of value to the other. Each could have expected to have a right to get the courts involved if the other reneged.

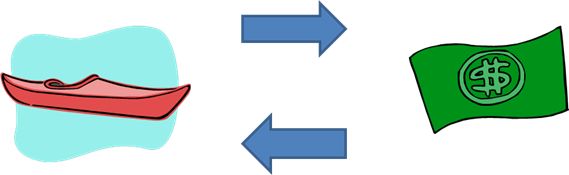

Here’s a simple illustration of the flow of consideration:

You can see that each party is bringing something of value to the table, so there’s no question whether the contract is supported by consideration. Visualizing a transaction like this and making sure that there’s something of value going in each direction is a simple way to make sure that the contract is supported by consideration.

Did you ask the price? Did you say “OK, I’ll take it”? Then you had a contract! It was executory for as long as it took you to reach into your pocket and hand over the money, and take the kayak off the premises.

Contracts for services are a little different, usually. “$10 to shovel your walk?” “OK” is a unilateral contract; the shoveler has to do the job (that’s the consideration from that end) before I owe the ten bucks.

Vance: A technicality in a technicality!

Seems like a lot to pay for a used kayak. Must have been a good one. Or am I missing the point 🙁

I find it interesting that, under US law (I’m a Mexican lawyer), the consideration doesn’t have to be “fair”. If I decide to sell my car for $10 usd… there’s no way that I can then sue and claim that the price was unfair for me?

I’m a French PhD student specialized in contract law and I admit this is an interesting blog.

In France, the contract law contains an interesting concept usually compared to consideration : the “cause”. We don’t consider that a contract is by essence a bargain : the 2 parties can be engaged to perform something (contrat synallagmatique), but one can be engaged and not the other (contrat unilatéral). The obligation must have a cause, so in the contrat unilatéral, the only the debtor is the one to require a cause. The creditor doesn’t need it since is not engaged to perform something. For example, donation is a contrat unilatéral, because one is engaged and not the other.

I think I’ll follow your blog from now on!